The annual fire season in the Amazon will soon be upon us and, as flames tear through virgin rainforest, cries of protest will once again ring out across the globe about Brazil’s indifference to the disaster. And, just as predictably, the hard right government of Jair Bolsonaro will claim it is doing all in its power to protect this unique environmental treasure, writes Alan Riding.

Bolsonaro is of course lying. In the 30 or so months since he took office, he has encouraged cattle and soya farmers to clear and burn forested land owned by the government or Indigenous communities in order to expand their production. Unsurprisingly, the deforestation rate in Brazil’s Amazon region in 2020 was the highest in a decade.

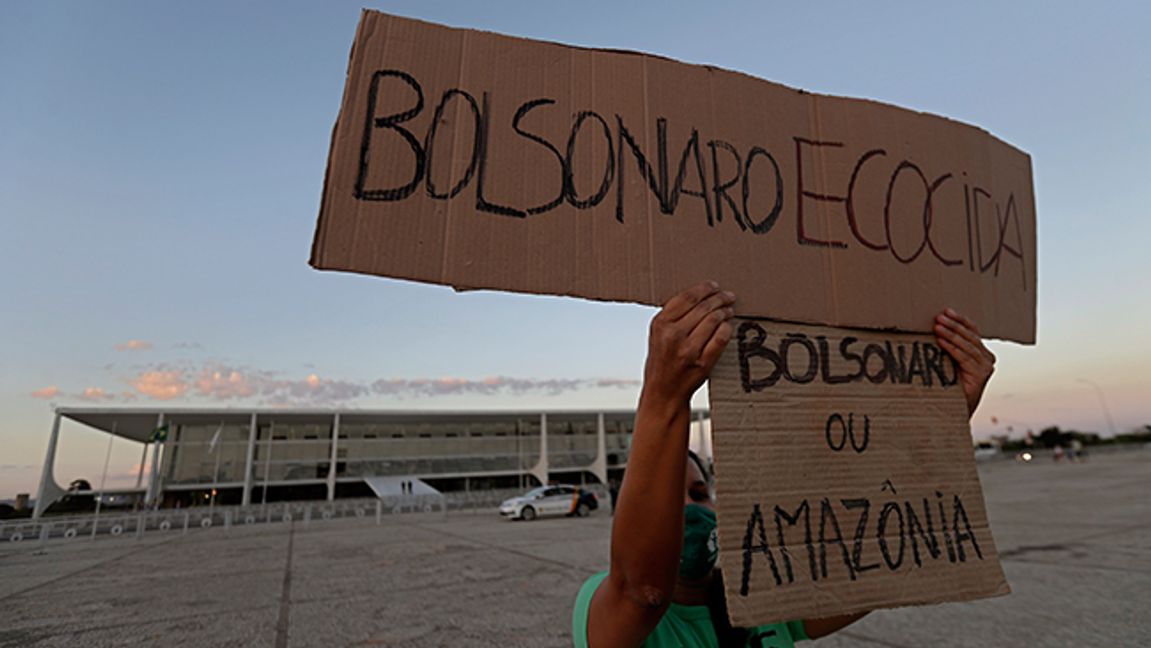

Workers from Brazil’s state-run environment agency IBAMA check an area consumed by fire near Novo Progresso, Para state, Brazil. Archive picture. Photo: Andre Penner/AP/TT

Bolsonaro has also turned a blind eye towards the illegal invasion of Indigenous territories by freelance gold prospectors who poison rivers with mercury, used for separating gold from mud. Further, with the government abandoning past controls on illegal logging, the export of valuable hardwood is now booming.

Add Bolsonaro’s irresponsible handling of the Covid pandemic – which he continued to play down even as the death toll mounted – and Brazil has taken on the image of a land caught in the grip of crime, corruption, poverty, sickness, violence and deep underdevelopment. All this in what is also the eighth largest economy in the world.

But while Bolsonaro likes to boast that “the Amazon is ours,” many abroad now strongly disagree, viewing the rainforest’s impact on climate change as too important to be determined by a single country. As a result, governments, private investors and food importers are stepping up pressure on Bolsonaro to protect the Amazon. And they are doing so in a language that both politicians and businessmen in Brazil (and everywhere) understand: money.

For instance, Norway, which paid $1.2 billion into an Amazon Fund between 2008 and 2018 to fight deforestation, has said it will resume payments once Bolsonaro changes policy.

Similarly, ratification of a $19 trillion trade deal between the European Union and the Mercosur bloc, which includes Brazil, is dependent on reduction of deforestation. Major Brazilian food exporters have also been warned they may soon face boycotts of some of their products.

That said, urgent action may still be thwarted by the deep roots of the Amazon crisis.

For centuries, Portuguese colonizers, European immigrants and African slaves and their descendants hugged a narrow strip of territory along Brazil’s Atlantic coast. Then, in a daring move, to turn the population’s attention towards the vast untapped resources of the country’s interior, a new capital, Brasilia, was built in the late 1950s, purposefully located 1,000 kilometers from the sea. It would prove a watershed in the country’s development.

In the 1970s, seemingly bent on further rearranging Brazilian territory, a military regime hoped to resolve the entrenched poverty of the arid North-East by building a so-called Trans-Amazonian Highway to encourage peasants to open new farms inside the forest. But the initiative failed: accustomed to desert life, the peasants hated the permanent humidity of the rainforest and instead migrated south to already-crowded cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

In contrast, small farmers and peasants in southern Brazil, desperate for land of their own, started moving north, eating away at the edge of the Amazon forest and moving steadily deeper into the jungle. By the 1980s, with new roads attracting gold prospectors and logging companies, the Amazon was evoking for many the El Dorado that South Americans had long dreamed of.

The first losers were Brazil’s Indigenous peoples, with a population that once exceeded five million and was now reduced to some 350,000 to 400,000 natives, divided into some 200 tribes. Victims of diseases and violence brought by outsiders, some ethnic groups were even exterminated. Coincidentally, albeit unrelated to the plight of the natives, scientists around the world began ringing alarm bells about the pace of deforestation.

By the dawn of the 21st century, then, the battle lines were drawn: environmentalists, defenders of Indigenous peoples’ rights, botanists, climatologists and the like faced the moneyed might of powerful meat, soya bean, mining and timber lobbies as well as politicians in the pay of illegal gold miners. Well before Bolsonaro further tipped the balance, it was already a one-sided affair.

How could it be otherwise? As the world’s largest exporter of beef, chicken, soya beans, orange juice, coffee and sugar-based ethanol, Brazil’s entire economy leans heavily on primary products. Naturally those who bring this immense wealth to Brazil wield enormous political power. And if collateral damage includes increased deforestation, well, so be it.

The truth is that, with the country’s wealth concentrated in the south-east, 4,000 kilometers from the heart of the Amazon, most Brazilians care little about the rainforest and even less about its native inhabitants. For these city (and slum) dwellers, the fires in the Amazon are no more worrying than those in California.

That said, between 2002 and 2010, the government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva did pay heed to the Amazon and its inhabitants. Many Indigenous tribes were granted exclusive rights to occupy large stretches of land while enjoying the protection of the long-respected National Indian Foundation, or FUNAI. And thanks to police and army actions, annual deforestation slowed to about one-third of 1990s levels.

President Bolsonaro then turned back the clock. Even during his campaign, he poured abuse on those defending Indigenous peoples and accused those fighting deforestation of blocking Brazil’s development. After taking office on January 1, 2019, he stripped FUNAI and the Environmental Protection Institute of much of their power and gave the green light to farmers to set fire to the jungle and miners to invade Indigenous lands.

In another era, the world might have overlooked this, but the climate crisis has placed the Amazon at the heart of the debate. Specifically, the rainforest’s unique ability to absorb carbon dioxide – a key factor in global warming – is being threatened by increased deforestation. Already the ground temperature of the forest is rising and rain patterns have been dangerously disturbed. Scientists have even warned that deforestation is driving the Amazon biome towards a “tipping point” at which the tropical jungle becomes a savannah.

So there is urgency.

Until recently, however, Bolsonaro brushed off foreign criticism as hypocritical meddling by countries that have already cut down their own forests. In 2019, when some Hollywood celebrities led by Leonardo DiCaprio began funding environmental action groups in Brazil, Bolsonaro even went as far as to accuse them of lighting the Amazon fires.

Today Brazil’s nationalist posturing looks more vulnerable. Thanks to campaigning by such vocal non-governmental organizations as Amazon Watch, large European meat and soya bean importers and their financiers are hurrying to disassociate themselves from products linked to deforestation. Brazil’s meat giant JBS has been singled out for exporting beef from cattle grazed on deforested land, while European supermarket chains are now wary of buying Brazilian beef. Fearing a customer backlash, three Brazilian banks – Itaú Unibanco, Bradesco and Santander – have joined forces to finance sustainable development projects in the Amazon.

More recently, having lost an ally in the White House, Bolsonaro is still further on the defensive. At President Biden’s climate summit in April, Brazil’s demand for massive foreign aid to fight deforestation was dismissed as grandstanding, all the more so since one day after the summit, Bolsonaro cut the Environment Ministry’s budget. On the eve of the annual burning season, the international community is clearly not about to reward Brazil for empty words.

Yet even after Bolsonaro leaves office – at the end of 2022 or, if re-elected, at the end of 2026 – the Amazon quandary will not disappear. Put simply, the Amazon rainforest can only be “saved” when its preservation is considered more profitable than its destruction. Its beneficial effects are apparent: for instance, so-called “flying rivers” carry immeasurable quantities of humidity from the Amazon that irrigate the entire southern part of the continent.

The rainforest, the world’s largest, also boasts a unique treasure of biodiversity representing around ten percent of the planet’s species, including a range of medicinal plants with curative powers still to be discovered. (Conversely, destruction of the natural habitat might release unknown pathogens capable of setting off fresh pandemics.) The rainforest is in turn rich in natural products that can be exploited in a sustainable manner, among them nuts, oils, fruits and the famed açai berry from the Amazonian palm tree.

For the Amazon to serve both Brazil and the world, then, it must count not only on bold leadership in Brasilia to forestall further deforestation, but also on private investment that demonstrates how farming, bio-industry and eco-tourism can give the rainforest far greater value than being razed for cattle. And here, Brazil’s critics also have a responsibility to propose creative solutions.

In all this, the natives of the Amazon perhaps deserve the last world. For millennia, they have learned to coexist with the forest, to live off its fish, animals and plants, without harming the environment. As guardians of the Amazon, they have much to teach us. And they are of more than anthropological interest. Through them, we can measure the health of the Amazon and, as such, the health of our planet.

Alan Riding was born and raised in Brazil and is a former New York Times correspondent in Latin America and Europe.