By allowing the European Central Bank to intervene directly and deeply in capital markets, the EU’s approach to climate change is violating basic principles of sound economic policymaking. Fortunately, its embrace of a once-maligned clean energy source shows that it hasn’t abandoned common sense altogether.

MUNICH – With its 2020 “taxonomy for sustainable activities,” the European Union found a way to use the European Central Bank to steer capital markets by directly subsidizing interest expenses for “green” investment projects. Many European politicians, especially those from Green parties in German-speaking countries, have applauded this approach. But now, they are dismayed to find that the European Commission, under pressure from France, will classify nuclear power as a type of green energy.

Having emerged from the anti-nuclear movement, today’s European Greens never dreamed that this ostracized source of power would not only regain respectability but even be associated with their own brand. Their humiliation couldn’t be greater.

But whether nuclear power is a form of green energy isn’t just a question of ideology. Huge sums of money are at stake, because the ECB will be offering banks particularly attractive refinancing conditions if they use EU-classified green bonds as collateral. The ECB also has made clear that it is more willing to buy up a disproportionate share of green bonds, thereby creating a new interest-rate structure within capital markets. Now that environmentally friendly investment goals are increasingly benefiting from lower interest rates, significant portions of Europeans’ savings – accumulated over generations – are being diverted from other parts of the economy into projects classified as green.

Viewed from the perspective of an economist, this is quite hair-raising. We are seeing a wholesale redirection of capital – the most important non-human factor of production in a market economy – and it is being done in a way that blatantly violates the principle of allocation neutrality, a key postulate of economic theory.

The economics of environmental externalities is straightforward. If the aim is to internalize negative externalities into the market – a worthy goal – it should be done through a direct pricing mechanism like a carbon tax or an emissions-trading system. By contrast, changing the interest rate – that is, the price of capital – merely invites a slew of costly allocation distortions, because capital, as a production factor in green enterprises, has only a very loose complementary relationship with avoiding environmental damage. Europe’s current approach therefore amounts to a scatter-shot policy.

The EU’s Maastricht Treaty does not give the ECB the authority to engage in economic and environmental policy; rather, monetary policymakers must secure an individual authorization and an extension of their remit. Such an extension requires unanimous consent from all EU countries by means of an amendment to the Treaty. This barrier should have ensured that the principle of allocation neutrality was upheld. But, as so often happens, EU policymakers have come up with legal trickery to avoid a formal Treaty change.

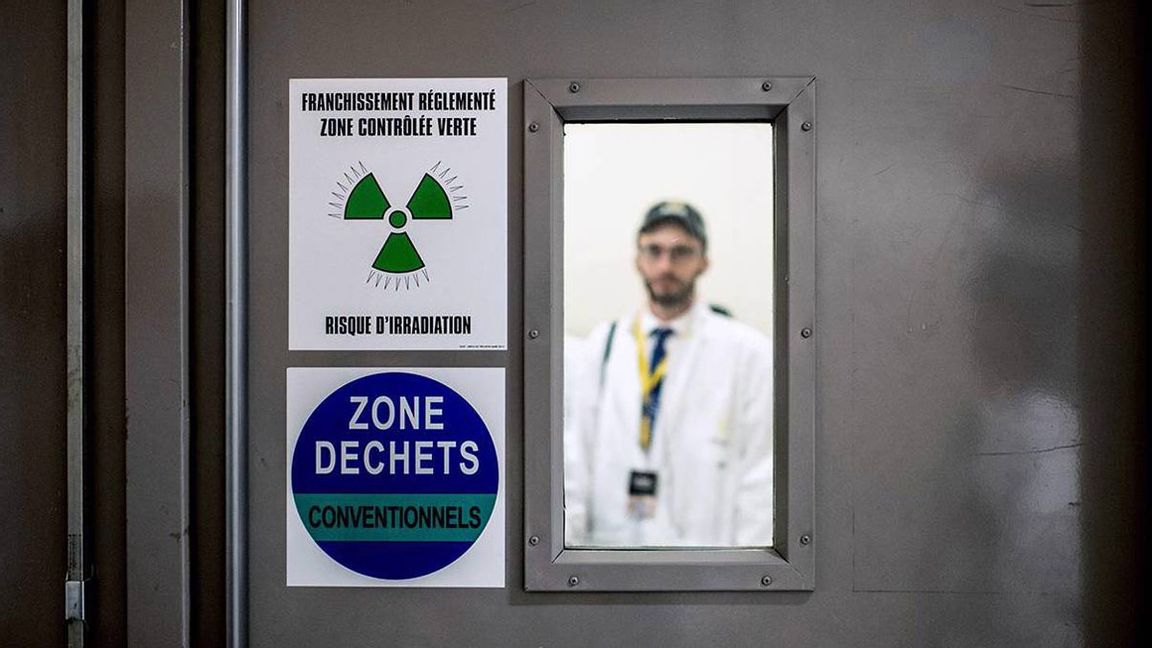

Putting aside the fundamental legal and economic concerns about the ECB’s manipulation of interest rates, the prospect of nuclear power receiving a green classification is a welcome development. It also makes perfect sense, considering that nuclear power plants don’t emit CO2. In terms of the broader climate agenda, Green politicians made a huge mistake when they demonized nuclear power, and the rest of the world has recognized this.

After all, the big shift away from nuclear power, and toward wind and solar, occurred only in Germany and a few other countries, following various accidents that received a great deal of media attention. New nuclear power plants are once again being planned and built throughout the world. Fifty-seven are currently under construction, 97 are planned, and 325 additional plants are being proposed.

The first country that seriously considered abandoning nuclear power entirely was Sweden, following the 1979 Three Mile Island accident in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. But it has kept most of its nuclear power plants, and it has long since given up on an exit. Similarly, despite the 2011 Fukushima accident, Japan has once again fully embraced nuclear energy, following a safety review and modernization of its power stations.

Even more promising, there is ongoing research into new types of nuclear power plants, including designs based on thorium and models that avoid the old nuclear-waste storage problem by using reprocessed fuel rods. These are inherently safer than the old power plants.

Viewed in this global, twenty-first-century context, Germany has become the wrong-way driver on the Autobahn. No wonder the Greens are internally divided. Most of them are still fuming, but some of the party’s more astute members are secretly happy that nuclear energy is available as a cheap, CO2-free alternative to fossil fuels. With its adjustable energy supply, nuclear power will be crucial for those periods when a protracted wind or solar lull threatens to bring electricity generation to a halt. Best of all, German Greens can save face by simply blaming the French.

HANS-WERNER SINN

Hans-Werner Sinn, Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Munich, is a former president of the Ifo Institute for Economic Research and serves on the German economy ministry’s Advisory Council. He is the author, most recently, of The Euro Trap: On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets, and Beliefs (Oxford University Press, 2014).